“Under Construction”

A note from Michele

This is an excerpt from my as-yet-unfinished memoir, which explores food and drink as throughlines in my life. My mother’s gingerbread houses — excuse me, Gingerbread houses — are a huge part of that story. The processes of planning and building them showed me the exact crossroad where tenacity and creativity meet. (Funnily enough, the best chefs, winemakers, and somms I know tend to be found at the same crossroad). They showed me the space between “have” and “have not,” which I call “have-a-little-but-share anyway.” The Gingerbread, everyone called it back then, became pretty famous in my corner of East New York, along with my mother, as the lady who brought the innocence and magic of Christmas to a community that usually saw so little of it, even if it was for only a few days.

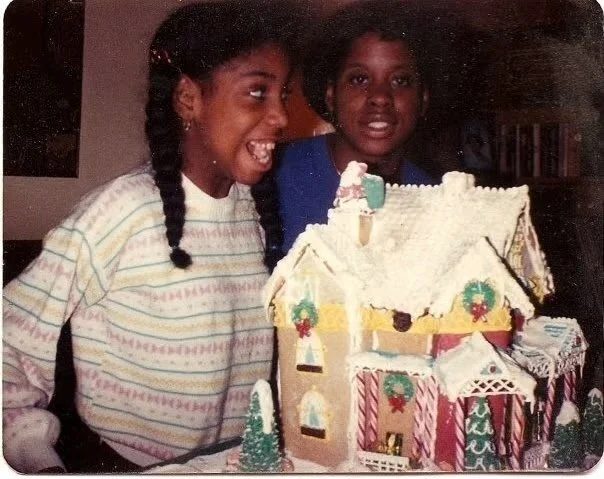

With my older sister, salivating over Gingerbread 1983

“Fucking gingerbread,” Chef Jurgen said, jacket open and sweaty after teaching Classic Pastry Arts for six hours, his pale skin and uniform almost blending into one of the long white table in the Chefs’ Office where he sat, sketching. Colored pencils and his mop of black hair were all that set the Associate Director of the Pastry Department apart from his surroundings.

“What’s cooking?” I had asked him moments earlier, entering the office and passing along the other side of the table towards the printer. Since joining the French Culinary Institute’s education department a few months ago, I’d adopted this as my customary greeting for the chefs.

Chef Xavier, also sweaty but from the Culinary department, glared impatiently from the computer station on the other side of the office. He’d swept into my office moments earlier, smelling like salted chicken, to tell me that the printer was jammed. Again. Like Jurgen, he was in the middle of a double teaching shift, which meant he had about a 90 minute break between classes. He needed to print a handout for his class and he needed time for a few cigarettes outside. There was no time to wait for the IT department to fix the printer.

“I’m not IT,” I told him. I always told them that.

“But you know ze computer,” he said. “I don’t know zees shit.”

“Yes, Chef.”

I opened a few panels and cleared the errant paper. Squeaks and whirring gears told me Xavier would be happy again.

“Okay!” he said with a smile and clap of his hands. He rolled his body toward the printer to wait for his papers.

I turned to go back to my own work, but the soft browns and reds and greens of Jurgen’s drawings stopped me. I sat down beside him, my body suddenly heavy. I wouldn’t be able to avoid Christmas, with its jingling bells, snowy rom-coms, and photos of toasty family gatherings, for much longer, no matter how many happy hours I lingered at the bar to avoid going home. I’d have to figure out something to say when asked about my holiday plans. Roasting Cornish Hens I would eat alone didn’t sound so festive. Neither did saying that I was estranged from my father and sister, and had been since my mother died.

Gingerbread houses always made me think of my mother. Christmas always made me think of the family I used to see gathered in my own photos of toasty holiday gatherings.

Almost everyone in the pastry department could draw, but Jurgen’s lines reminded me the most of my mother’s. I could see the formal training in both, the light strokes, swift moves that slowed down as the confidence in their line placement grew. I looked at Jurgen’s hands filling in buildings and windows.

“My mom used to make gingerbread houses,” I said.

“Oh nice,” he said in Austrian-accented English. NiiCE. I instantly felt stupid. I wanted to make him understand. Gingerbread―and that’s how I say it, with a capital “G”―is a time, an event, maybe even a place, and, at its simplest and purest, a housing project, an inversion of the one I grew up in out in east Brooklyn. A pastry art. Not something made from a kit.

“I mean, big ones, like this.” I tried to recover. “Not, like, the ones from Costco or whatever. Is this for the 4th floor display?”

Jurgen leaned back in the chair and looked at me. The sweat was drying, giving him a dewy sheen. He ran his hands through his hair. “This is really big. It’s for L’Ecole. We do a big gingerbread every year,” he said. “I mean, I do like it. It’s Rockefeller Center and the students volunteer and it’s very good for them. It’s just a pain in the ASS.” He smiled and turned the sketch toward me. “Top of the rock! They want more color, so I’m redecorating.”

“Oh nice,” I said. I was curious now. L’Ecole was the school’s Michelin-rated restaurant and where I spent happy hour most nights after work. I wondered where they’d fit a gingerbread house down there. My mom could have made Rockefeller Center out of Gingerbread, I was sure of it. One year, she made a small town of six houses with a bridge over which Santa and his reindeer drove a sleigh. In another, she made a train station, complete with multi-car locomotive and a Gingerbread soldier the size of a Pringles can.

“Chef Juurrgen!” A Queens accent echoed from the hall just outside of the office. Chef Cynthia loped in, her clogs thunking beneath her. “Chef Jur-oh! There you are. I can’t find the gold leaf. Do we have any more?”

“Check the storeroom. Ask Bear,” he said, then leaned toward me. “You should come see the gingerbread! We’re working on it tonight. Come to the kitchen.”

***

After work, I grabbed my usual seat at the far corner of the bar in L’Ecole, closest to the window and the least in the way of the guests who’d made actual dinner plans. I had a full view of the dining room, painted cream with oxblood trim and banquettes. On the walls were frosted sconces and photos of prestigious chefs with students: Bobby Flay’s graduation photo with Julia Child, Alain Sailhac, André Soltner and Jacques Pépin smiling benevolently over the dining room—many of the staff referred to Chefs Alain, André, and Jacques as the father, son and holy ghost of Culinary Arts. I could see the doors that led to the kitchens, where the gingerbread house was under construction. I sipped on my favorite cocktail — a blend of vodka, lychee puree, ginger and lime juice called Fire & Ice — while working on the courage to step into the kitchens. I was a suit, working in an office, worse than front-of-house. I didn’t belong back there. At least this is what I told myself. In truth, I was afraid the pastry department’s Rockefeller Center would blow apart every house I’d ever had, and with it somehow my sense of being good enough to move around in this world. I didn’t even like Rockefeller Center.

I’ve never lived in a house, but I had one, made out of gingerbread, every Christmas for sixteen years, for about four days. We all did: me, my sister, my parents, a few extended relatives, the neighbor kids and their parents—well, some of the parents, anyway. Some of them you wouldn’t let into your apartment because they’d steal your shit, or worse, tell everyone what you didn’t have. Our house was decorated with candy and royal icing windows that could shatter like glass and families, set in the middle of a snowy, sugary yard, in the middle of the living room of my family’s two bedroom apartment.

The first house was simple enough. A gingerbread cabin with a sloping roof and a chimney that was designed to look as though it would fall off, taken from the pages of whatever magazine my mother picked up from the checkout line at Pathmark a few weeks before. The trees were made of gumdrops, the front yard was lined with candy canes, and white children made of paper watched us from every window while a cookie-cutter gingerbread man stood by the fence, guarding the property. Royal icing swirled across the yard, just past the fence, fading into aluminum foil that wrapped the corrugated cardboard base of the property. The fence and chimney were gingerbread baked with sliced almonds, and, like the rest of the house, were dusted with powdered sugar. “Merry X-Mas,” read one side of the roof in red frosting. “To all a good night,” read the other. The house looked desperately happy, a shadow of sadness around the edges, under the eaves. It looked like we did that Christmas, barely three months after my grandmother died. My mother didn’t know what to do with the grief, so she made us something to eat. I was little, a few months into kindergarten, and don’t remember exactly how long it took her to make that house, but I am sure it was less than a week. It was always less than a week, and always finished by Christmas Eve.

“God built the world in seven days,” she’d say. “This damn well gonna be done in six.”

“What the FUCK are you doing out here?” Jurgen’s voice snapped me out of my memory. Somehow, I’d missed the approach of his 6’3” frame, clad in white and flour spattered black pants. “Come see.”

“I was getting a drink first!”

“You can order another one later,” he said, throwing an arm around my shoulders. “Come, and then I can join you at 8.” It was 5:45. I’d hoped to be home by 8, or at least on the subway. But I scooted off the stool and said, “Yes, Chef.”

“Pfft,” he said, leading me across the dining room toward the kitchen doors. “Don’t ‘yes chef’ me. I hear that all fucking day. God!”

You’ve got to move with purpose when walking through a kitchen. I had to almost run to keep up with Jurgen’s long strides past the saucier and garde manger stations on the way to the pastry kitchen.

“Civilian!” Chef Xavier yelled at me across the pass. “What you do back here?” He was to expedite for the Level 5 class that evening.

“Ordering fries?”

***

Muffet, our mostly beagle mutt, ate the gingerbread man sentry while my mother, sister, and I were at the midnight Mass that officially started Christmas (my dad was supposed to be watching the dog, but he fell asleep, the work day that started at 8am wearing on him), but the rest of us had to wait a few more days to get a taste. There weren’t many of us that year, just my sister and I, our neighbor Jacqueline, and her mother, Mary, from the building next door, and Ms. Connie, who was probably mom’s best girlfriend, and her kids. I don’t even think Ms. Peggy the Crackhead and her girls were there that year. I remember we posed for pictures in the living room before my mother ferried the house back to the kitchen table, where the dog couldn’t reach. And I remember the countdown.

“Ready, set,” my mother said. “One. Two. Two and a half. Two and three quarters. THREE! Go!” Somewhere between ten and twelve gingerbread-colored hands flew toward the house, sugar-snow flying, and ripped into that house with the force of a thousand tornadoes and the kind of savage glee that only children in the presence of unregulated sugar can muster. Cameras snapped, flashes like lightning, and a mixture of child and grownup laughs thundered through the kitchen and bounced off the walls. It was biblical.

I remember that my sister got the chimney. Ripped it clean off. I got a chunk of the roof with its merry red frosting letters, a bit of cabin wall—I remember how my mother used a paring knife to score lines in the gingerbread dough just before baking to make it look as though it were made of logs—and a chunk of the rustic nut fence. I picked away the bits of royal icing that held the structure together and shared some of them with Muffet, who sat drooling under the table. My mother peeled away the paper child icing-glued to the window, clucking her teeth, before letting me chomp my way through her construction—the windows would be different next year. I can’t speak for what the other kids took with them, but I know they carried it home in one of the sandwich bags my mother always kept in the cabinet with the pie dishes. Every kid got one sandwich bag. Siblings got two if they shared.

After the dust settled and us kids were sugared to exhaustion, the house lived on for another week or so in a series of vessels—the big orange bowl normally reserved for bread and chocolate chip cookies, and then, after few days of regulated afternoon snacking, or my father’s unregulated night raids, the great glass cookie jar that lived on the kitchen counter.

That jar was rigged, there was no way to open it silently. My sister and I tried for years. Barely touching the lid was always followed by my mother’s voice from down the hall. “Put it back,” she would say.

Christmas had been captured, crafted even, and brightly decorated to make it stand out in the dark.

Photo courtesy of Michele Thomas